User:Soberm

The rise of “the Enemy of the State” to global power

Facebook, which emerged as thefacebook.com, was launched by a group of Harvard students in 2004. The group was led by Mark Zuckerberg, who chose to call himself “the enemy of the state” in his first profile description on the platform. The initial goal of the online service was to create a space for Harvard students to interact with each other through personal profiles. The platform gained increasing interest and first, spread to other Ivy League universities, and then turned into a widely used service among educational institutions at national level in the US. In 2005 Facebook became available to international educational institutions, while in 2006 significant changes to the creation of profiles were introduced. These changes enabled a wider audience to join the platform regardless of their occupation and nationality. Until 2007 the creation of Facebook profiles was limited to just individuals, while the new features launched in 2007 made it possible for anyone to create a page, which in turn led to the rise of usage of the platform by stakeholders from all societal sectors – public, private, civil society [1].

Since its inception Facebook developed a diverse number of functions and services and what started out as a platform to connect students in the US became a big multinational corporation expanding its influence into new areas of the economy and life. While it rose to become one of the most powerful social media platforms globally, its popularity also became the reason for an increasing interest of state actors to define limits of Facebook's power.

The power of Facebook data

Agree to Terms and Conditions, how often do we just click the button without thinking about the consequences? Because who has the time to read the lengthy explanations for cookies, apps, and social media accounts? If everybody who uses Instagram accepts these terms and conditions, they cannot be too bad. This is a common human error called the bandwagon fallacy, where one assumes that if others carry out an action, they can as well Too few users question what traces of personal information they leave in a vast digital world and are thus unaware of the power they give to the companies responsible. Whether we consider Windows, Apple, or Facebook, in the information society we live in, the amount and quality of data equates to power. The most valuable information is personal data and Facebook has access to more of it than most other companies [2]

The Dark Side

Users need to agree to the conditions set by Facebook to use the website, thus giving them the authority to manage user-data. Facebook’s policies are constantly changing, additionally it makes a difference whether the user is American, European or from any other country, as laws and regulations limit Facebook’s power differently. Whilst American citizens are barely protected against data misuse, the EU constantly tightens their laws to ensure the security of the data. Thus, European Facebook users’ data is less prone to be violated. However, Facebook does share data with other businesses, more than just the public aspects of a profile. According to an article in the Guardian, in 2018 Facebook admitted to having given “special rights to information” to over 60 companies, such as Nike, Spotify and Amazon [3]. Despite increased public pressure, Facebook has yet to specify the exact content that was shared. Facebook's policies were put on the spotlight in 2016 when it was uncovered that Cambridge Analytica, a British data analysis provider, accessed the personal data of over 87 million Facebook users [4].

Furthermore, the company claimed to have influenced the 2016 presidential election on behalf of the Trump administration [5]. The business offered an app through Facebook which legally gave them access to all 270 000 users who downloaded the software, however through a loophole in Facebook's security measures, the account information on all the friends were also retrieved. Thus, Cambridge Analytica had access to over 50 million US Facebook accounts. Experts argued that, using the methods of Cambridge Analytica, entirely changing a person’s belief was not possible, however certain behaviors could be provoked. The profiles were used to identify potential Trump and Clinton voters to create specific advertisements, posts and in this case also fake news, to either convince a potential Trump voter to vote or a potential Clinton voter not to vote [6]. Personalized advertisements have been used earlier in politics as well, Obama used it for his campaign, and they are legal. The method is called microtargeting and is constantly used by all media moguls for advertisements or to keep the user hooked to the screen. In the case of Cambridge Analytica, the data was obtained in an unauthorized manner and furthermore was employed to manipulate people.

If Cambridge Analytica’s methods are effective it becomes evident that with the amount of personal data held by Facebook, they also hold a lot of power as they can influence actions of individual targets. Facebook allowed the data mining to continue, even though they noticed the issue in 2015, they eliminated the app in 2016 and the business account was not suspended until 2018 [7]. Although Kogan, from Cambridge Analytica, confirmed having “destroyed” all the data, there are multiple allegations that the process is not yet complete. Facebook lost control over personal data and was not able to ensure its deletion, thus one needs to consider whether Facebook should be allowed to wield such power, that can be pivotal in presidential elections, if it cannot ensure its security.

The potential Good side

Digital data profiles are not limited to exploitation but have the potential to be used for constructive actions. A study from 2018 suggests that Facebook activity can be used to predict the mental health of an individual [8]. This could help people suffering from depression, a mental health issue of increasing occurrence, of which too few cases are diagnosed. However, the use of Instagram and Facebook has proven to be harmful to mental health, despite being aware of it, Meta has not implemented any measures to counteract the impact of the platforms. Only the surface of the capabilities of personal data have been scratched. It is the manner these possibilities have been explored, which makes the users feel as if their data was violated and unsafe. The participants of the study consented to the use of their data; most people affected by Cambridge Analytica had not.

Another aspect for which Facebook data could be used is to counteract online presence of terrorist groups. In 2018 Facebook reported on their actions on counter terrorism, explaining how they applied their new machine learning tool, to recognize language patterns and potentially terrorist posts [9]. In their report they gloated about the success their system had achieved in only a few months, however in recent years it has become evident that the system is somewhat superficial and focused on the Arabic language. According to an article from 2021, journalists from Syria and Gaza were repeatedly censored, whilst hate speech was shared in Myanmar and India [10]. In the case of counterterrorism measures, mainly posts are targeted, and the Facebook data profile is not developed, as otherwise Facebook would have to admit to the use of such information. However, in the case of terrorism and other crimes, would it not be constructive to have access to data profile to inhibit any violent actions? Then users would have to give Facebook permission and allow the company to use their data, for the terrorist screening to be done legally and ethically. That would not be realistic as most users do not want to have a company storing their online actions and developing a profile based on psychometrics. Furthermore, one could argue that if the users were aware of such supervision, users such as terrorists and criminals would not use the platform. Experts constantly question the potential of digital profiles. Possibly there is no algorithm that can detect criminal intent from the digital profiles, it would require scientific, large-scale experiments to determine the effectiveness. With the intention of protecting people and reducing crime, could Facebook or another company use data profiles without the consent of its users?

This leads to one of ethics oldest discussions: do the intentions or the consequences matter. A utilitarian would argue that the using the data without consent would be acceptable only if terrorism was prevented, however not if no crime was stopped. Whilst in accordance with the good intention’s theory of Kant, independent of the outcome, if the data was just used to try to counteract crime the actions are ethically justified. Topics concerning the security of people should possibly not be handled by a money drive company, but by a governmental institution, but would Facebook then have the right to share the data?

The discussion of what the data would be used for has an impact on the discussion whether the data should be stored at all. Users are unaware of the Big Data that Facebook controls and not educated on what their actions on the platforms result in. Additionally, most users are unaware of the unexplored potentially good or bad uses of the data. The battle for an individual’s privacy must be fought on several fronts. The awareness amongst users about these issues needs to increase, furthermore Facebook should provide clear information about what data they have and what they share with whom. Facebook will not do this voluntarily; it will require pressure from governing institutions for Facebook to subdue to the rules.

Meta - a sly rebranding for a monopoly on our reality

Last October of 2021, Facebook became Meta. A complete rebranding of the company that owns Instagram, Facebook and WhatsApp is now under the umbrella company Meta. For most of the world’s population of these three social media users, perhaps this rebranding would’ve gone unnoticed by the general masses if it weren’t for the media quickly picking up on it.

Most of what was widely covered were not the feature releases but instead the peculiarity and even the overarching idea of what was really being sold: the metaverse.

What is the Metaverse?

The term first appeared in Neal Stephenson’s 1992 sci-fi novel Snow Crash, in the following passage:

“In the lingo, this imaginary place is known as the Metaverse. Hiro spends a lot of time in the Metaverse.”

Who wants the Metaverse?

In his launch video, Zuckerberg says that “meta comes from the Greek word from beyond”. Etymologically, meta meant “after” in Greek. But who asked for this ‘beyond’?

When we think about the future as infinite branches of possibilities, where each branch is a path we can take as society, what happens when there are massive investments from big tech that go under the radar, is that these possible paths are no longer chosen by us, but by a restricted group of people, somewhere in Silicon Valley.

In order to analyze where this fascination for the metaverse comes from, we can try and pay attention to what it was like before Zuckerberg appropriated the term Metaverse and try to trace back other sources of genuine interest in the topic. We can maybe trace back a connection to Virtual Reality becoming popularised, and maybe even spaces such as VR chat, which could be an example of what the Metaverse will look like, in Zuckerberg’s vision.

According to Merriam-Webster[11], some uses can be traced in the following excerpts:

As a synonym of multiverse, meaning “a theoretical reality that includes a possibly infinite number of parallel universes.” With its hegemony diminished, universe has given way to other terms that capture the wider canvas on which the totality of reality may be painted. Parallel worlds or parallel universes or multiple universes or alternate universes or the metaverse, megaverse, or multiverse—they’re all synonymous, and they’re all among the words used to embrace not just our universe but a spectrum of others that may be out there. — Brian Greene, Discover, 2 August 2011

Referring to the “space” of the experience of virtual reality, including such real-world uses as the training of pilots:

Viewing virtual objects from different angles and perspectives, participants of aircraft metaverse can interact with 3D assets and have hands-on experience. — Aziz Siyaev and Geun-Sik Jo, Sensors (Basel) Vol. 21, Iss. 6, (2021)

And in economic discussions, where the digital world is a possible business environment: ...some proponents believe that blockchain technology and decentralised apps will be the keys to unlocking the next big leap forward for the Web: the metaverse, a place where augmented and virtual reality, next-generation data networks, and decentralized financing and payment systems contribute to a more realistic and immersive digital world where people can socialize, work, and trade digital goods. —Ian Bremmer, Foreign Affairs, Nov.-Dec. 2021-

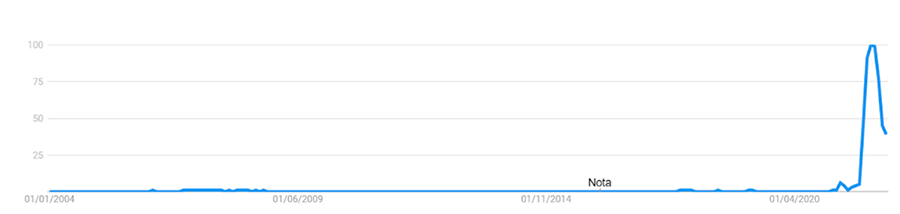

We can also look at other sources, such as the searched interest in metaverse through time (Worldwide, since 2004), through Google Trends:

Comparative graph with other terms:

‘Metaverse’ – blue ‘Virtual reality’ – red ‘VR chat’ – yellow

VRChat was released to the Steam early access program on February 1, 2017. So it only shows up on the graph after it’s released, naturally. Virtual Reality has a completely different pattern of interest than the ‘metaverse’ which hints that the sources of interest are different, if not completely. Nonetheless, based on the disconnect of these terms presented on the graph, the idea of creating artificial interest in the masses through investment is reinforced, which is one of the many powers of privately owned platforms.

Why did Facebook turn into Meta

One can speculate that the rebranding was an attempt to reset the reputation of Facebook after the Cambridge Analytica scandal, where even the ticker in stocks has changed from “FB” to “MVRS”. In a sense, it could be an attempt to respond to the plummeting stock investments in Facebook[12], and also continue eradicating competition, and to remain a natural monopoly[FOOTNOTE], as the company dedicates $10bn in 2021 to Meta’s metaverse [13]. When faced with this early-on investment, what chances do alternate emerging or already existing virtual spaces have to compete?

One simple but highly effective evidence of Meta’s monopolizing is exactly branding this virtual space as “Metaverse”, excluding all other virtual spaces of being also considered metaverse or, in a sense simultaneously to eventually include all these different virtual spaces under the umbrella of Meta.

The word ‘metaverse’ existed before Meta which means Zuckerberg did not create this term, he appropriated it. This could parallel to hypothetically naming a company with something so universal and completely outside the private realm such as ‘music’ and naming it Music®. Besides, when we think about Facebook (and technically all the other social media platforms owned by Meta) it all began as a social media platform that has slowly but surely turned into the default medium for human social interaction.

What is Meta’s metaverse

Now that we’ve looked at various interpretations of metaverse, what is Zuckerberg’s appropriation or interpretation of this? From what has been communicated so far, the metaverse will go hand in hand with microtransactions, cryptocurrency and the NFT market, but we also noticed a big focus in the workplace adaptation to these virtual spaces. SOURCE

Seemingly so, history will repeat itself, as Meta plans to develop everyone’s metaverse, to be the overarching private, closed-source company that will aim to become the default platform that will hold future services such as the game industry, other diverse applications of augmented reality and virtual reality, and any other private sector might want to invest hop on this trend. All while taking little risk and almost zero effort. (Will public services also be incorporated in this metaverse?)

This is merely the continuation of the evolution of capitalism into platform capitalism, which according to Nick Scrnicek [14]. , is minimum-effort capitalism where huge companies create the intermediaries that host and connect the buyer to the seller. Traditionally, these would be physical shops, stores, but the difference here is the sheer dimension of which these platforms have taken form, and redefined the way that capitalism continues to evolve in our modern world. It would be as if the whole farmer’s market ground where some small farmer has their shack to sell potatoes was suddenly owned by a private company and not publicly managed by the local council.

How will security concerns be implied in Meta’s metaverse?

When we think about data, a privately owned Metaverse means not only a privately owned platform where you communicate with your loved ones, work, and express your thoughts and opinions. In a privately owned metaverse, what is privately owned is not only a platform restricted to the physical confinement of your phone or computer, but yes, the visual space you are inserted in. Although dependent on how intrusive this Metaverse will be, the sphere of influence that Meta will have, will directly affect your visual perception of reality. One can even joke that in this virtual space, you will be walking to meet your virtual date but before you can do so, you must sit through a non-skippable ad.

Not only the level of immersion will be higher, so will the level of intrusion. A successful metaverse is as any other technology, an extension of the self [15], so if the Metaverse were to, for example, not cause nausea after extended use of the virtual headset and the user experience were to be seamless, then the headset we are using would become invisible, as well any other technology inside the virtual interface would become irrelevant to the task performed-say you would be playing virtual poker, the task would just become playing poker. And in that moment, is where it could become more dangerous.

These days, platforms such as social media are being used as battlegrounds for literal wars and cyberwars, propaganda and genocide. One can only imagine the subtle messaging that could be introduced in a privately-owned metaverse as well as product placement and targeted advertising, where the user is so deeply immersed.

Facebook: A threat to the state or a victim of the states

Bans on Facebook

With the rising reach of Facebook globally its political impact started becoming noticeable as also shown by the examples previously. While democratic countries have also censored content on Facebook, most of the action taken against the company was driven by autocratic states in their efforts against civil society unrest and oppositional forces. Multiple countries have placed temporary and some even permanent bans on the social media platform.

The first country to ban Facebook was Iran in the lead-up to its presidential elections in 2009. The social media platform was blocked in the effort of the Iranian government to suppress the voices of the opposition, as the platform connected the leading oppositional candidate to critical youth [16].

Soon after the ban was introduced in Iran, China banned Facebook. The ban followed after deadly civil clashes in the province of Xinjiang which were attributed to mobilization online [17]. In 2000 a document of the Chinese State Council outlining categories that should be censored was released, where one of the points relates to the internet information services which promote hatred and racism among people [18]. Therefore, the activity of Chinese users on Facebook groups that facilitated the mobilization for the Xinjiang riots is in violation of that principle. The violence in the province of Xinjiang became the reason for completely banning Facebook in China [19].

While citizens of North Korea have very limited access to the Internet in general, Facebook got banned in the country in 2016. Due to the already restricted usage of the platform in North Korea the main reason to ban the platform is to prevent real-time publications by foreigners visiting the country [20]

Most recently, in the context of the invasion of Ukraine, Russia put a ban on Facebook and labeled Meta an ‘extremist’ company, whereby Facebook was seen as a platform promoting interests against Russia [21].

While the aforementioned bans on Facebook are driven by governmental efforts against oppositional forces, they can be seen as action taken based on the values held by the leaders of these states. In the same sense, the European Union has taken recent action against Facebook and other big companies, in an attempt to defend European values such as privacy, democracy and fair competition. The approach of the European Union is regulating such platforms and trying to achieve a change in behavior instead of banning them.

The EU's data protection concerns

The first big move against practices of Facebook and other big companies was the release of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). The GDPR was negotiated in the context of the Snowden revelations, which in 2013 exposed the large-scale surveillance campaign of the US based on data of multinational corporations such as Facebook. This event significantly shifted the attention to large companies and resulted in their demonization and subsequently in the adoption of a very strict GDPR, as the salience of data protection increased among Europeans and European decision-makers respectively [22].

While the Snowden revelations exposed a number of companies, Facebook became the center of European attention in the two legal cases driven by the Austrian activist Max Schrems II. Schrems filed data protection-related complaints against Facebook, which resulted in the Schrems I and Schrems II rulings of the European Court of Justice. These rulings invalidated existing agreements for data transfers between the US and the EU, which significantly complicates the work of American companies relying on such transfers. These processes became the reason for the famous statement of Zuckerberg that Facebook could leave Europe, as no agreement between the EU and the US on data transfers might make Facebook’s operation in Europe unprofitable.

“With size comes responsibility” – European Commissioner Margrethe Vestager [23]

At the end of 2020 the Digital Services Act Package was released by the European Commission and included two pieces of proposals for regulations – the Digital Services Act (DSA) and the Digital Markets Act (DMA), both of which have significant implications for platforms like Facebook.

The DSA establishes a number of rights of users online, as well as directly regulates different types of content distributed by digital service providers. The DSA also implies that the European Commission should receive access to the data of such service providers in order to track compliance [24]. The DMA, on the other hand, regulates competition and aims to ensure fairness among digital service providers by preventing unfair practices employed by big platforms acting as gatekeepers. Both regulations have been agreed on by the responsible EU institutions and will mean significant costs in case of non-compliance. However, it is worth noting that it will take another almost 2 years for the DSA to become applicable across the Union, while for the DMA it would be 6 months after it officially comes into force [25].

Despite enormous lobbying efforts, the EU is taking decisive action against companies like Facebook in the pursuit of protection of the Union’s values. Whether these newly introduced measures will have any effect on big platforms like Facebook remains to be seen as such companies possess the resources to cover even big fines, while the European regulatory apparatus is slow and might remain toothless in the fast-developing world of Big Tech.

Facebook's cryptocurrency Libra

This page is primarily concerned with the dangers of social media data collection. An interesting case with that is the new cryptocurrency “Libra” from Facebook. Most crypto currencies encrypt transactions, promoting anonymity and giving people back their privacy. But Facebook is notoriously known for harvesting user data. That does not seem to fit with cryptocurrencies. In this chapter we’re looking into the ideas of “Libra” and also look at the opposite of data protection: What are the dangers of anonymity on the Internet? In 2019, Facebook planned to create a cryptocurrency named Libra [26]. The plan was for the cryptocurrency to drive e-commerce ventures on its platform. Although Facebook is otherwise very well known for collecting and analyzing user data en masse, the company seems to be going in the opposite direction with its cryptocurrency. On June 18th, 2019, Mark Zuckerberg shared a long Facebook post about their crypto plans. He wrote “Libra's mission is to create a simple global financial infrastructure that empowers billions of people around the world. It's powered by blockchain technology, and the plan is to launch it in 2020” [27]. He claims that the Libra Association is built on blockchain technology and is decentralized – meaning it is run by many different organizations instead of just one. “This is an important part of our vision for a privacy-focused social platform - where you can interact in all the ways you'd want privately, from messaging to secure payments”. Facebook Libra aims to become the first mainstream cryptocurrency and allows all kinds of payments. The potential use cases for the cryptocurrency are peer-to-peer funds transfer, online payments, brick-and-mortar payments, and in-game/in-app purchases. “If all goes well, you’ll even be able to apply for a loan or credit” [28].

The problems with Libra

However, the Libra currency never really started. The project immediately ran into fierce opposition from policymakers globally, who worried it could erode their control over the money system, enable crime and harm users’ privacy” [29]. The Diem Association — which Facebook founded in 2019 to build a future payment network — was selling its technology to a California bank that works with bitcoin and blockchain companies [30] By that, “Facebook’s jump into crypto is over before it really began”. [31]

Cryptocurrencies and anonymity

Many analysts believe that Zuckerberg wants to create a U.S. version of the Chinese app WeChat, which combines social networking, messaging, and payments in one app [32] Facebook wants the same all-in-one app, only on a global scale. This will allow Facebook to display ads on WhatsApp and Instagram and let users pay directly for products and services through the app. If Facebook manages to institute Libra, it’ll be able to gather even more data on its users’ shopping preferences [33]. The US Senate is also concerned about the Facebook currency. Back in 2019 they sent Mark Zuckerberg a letter and asked him seven questions about privacy and data with the Libra currency [34]. They haven’t heard back from him since then and until they get an answer to their questions, they want to postpone the launch of Libra. So far, many people worry that Facebook is not that serious about data protection, especially when one thinks about Facebook’s past actions. Recently cited Deyan G. from techjury.net (2022) wrote about the Libra project and quotes William Shakespeare “Don’t trust the person who has broken faith once.” Facebook is “not the paragon of trustworthiness”. The Cambridge Analytica Scandal from 2018 is still fresh in mind for a lot of users. Back then, Facebook harvested user data from about one million users for advertising during elections [35]. Fears about a lack of data protection at Libra are therefore not unjustified.

Downsides of anonymity

In general, cryptocurrencies are known to offer more privacy than traditional currencies. But this privacy also has some downsides. The high anonymity favors illicit activities like money laundering, tax evasion, transfer of money to terror organizations, and demands for ransom by criminals [36]. For instance, the WannaCry malware, which infected many computers back in 2017, required victims to pay a ransom in bitcoins (ibid.). To prevent crimes like this it is necessary to increase the regulatory measures. The ability to transact anonymously is one of the most important attributes of digital currencies. “Nevertheless, the need to combat crime supersedes people’s desire to maintain anonymity in their online transactions. Therefore, cryptocurrency may face stringent regulations in the future” (ibid.). Although more people want to protect their data and governments are imposing further laws on data protection, online anonymity also leads to a perilous online world boosting crime and fake news, we are left with many and simultaneously no solution to one of the most critical challenges of the information society.

References

- ↑ Brügger, N. (2015). A brief history of Facebook as a media text: The development of an empty structure. First Monday.

- ↑ Www.idx.us. (2022). [online] Available at: https://www.idx.us/knowledge-center/personal-data-privacy-the-worlds-most-valuable-resource-and-how-to-protect-it#:~:text=The%20data%20universe%20will%20consist.

- ↑ staff, G. and agencies (2018). Facebook reveals it gave 61 companies access to widely blocked user data. The Guardian. [online] 3 Jul. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2018/jul/02/facebook-user-data-access-companies-privacy.

- ↑ Hurtz, S. (n.d.). Cambridge Analytica: Neues Jahr, neuer Skandal? [online] Süddeutsche.de. Available at: https://www.sueddeutsche.de/digital/cambridge-analytica-facebook-brittany-kaiser-1.4747594.

- ↑ ingo, tomas and Rebiger, S. (2018). FAQ: Was wir über den Skandal um Facebook und Cambridge Analytica wissen [UPDATE]. [online] netzpolitik.org. Available at: https://netzpolitik.org/2018/cambridge-analytica-was-wir-ueber-das-groesste-datenleck-in-der-geschichte-von-facebook-wissen/.

- ↑ Dachwitz, C.K. und I. (n.d.). Microtargeting und Manipulation: Von Cambridge Analytica zur Europawahl. [online] bpb.de. Available at: https://www.bpb.de/themen/medien-journalismus/digitale-desinformation/290522/microtargeting-und-manipulation-von-cambridge-analytica-zur-europawahl/.

- ↑ Hurtz, S. (n.d.). Cambridge Analytica: Neues Jahr, neuer Skandal? [online] Süddeutsche.de. Available at: https://www.sueddeutsche.de/digital/cambridge-analytica-facebook-brittany-kaiser-1.4747594.

- ↑ Eichstaedt, J.C., Smith, R.J., Merchant, R.M., Ungar, L.H., Crutchley, P., Preoţiuc-Pietro, D., Asch, D.A. and Schwartz, H.A. (2018). Facebook language predicts depression in medical records. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, [online] 115(44), pp.11203–11208. Available at: https://www.pnas.org/content/115/44/11203 [Accessed 27 Mar. 2019].

- ↑ About Facebook. (2018). Hard Questions: What Are We Doing to Stay Ahead of Terrorists? [online] Available at: https://about.fb.com/news/2018/11/staying-ahead-of-terrorists/.

- ↑ www.voanews.com. (n.d.). Facebook’s Language Gaps Weaken Screening of Hate, Terrorism. [online] Available at: https://www.voanews.com/amp/facebook-s-language-gaps-weaken-screening-of-hate-terrorism/6284394.html.

- ↑ Merriam-Webster. 2022. What is the 'metaverse'?. [online] Available at: <https://www.merriam-webster.com/words-at-play/meaning-of-metaverse> [Accessed 30 April 2022].

- ↑ Solon, O., 2018. Does Facebook's plummeting stock spell disaster for the social network?. [online] the Guardian. Available at: <https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2018/jul/26/facebook-stock-price-falling-what-does-it-mean-analysis> [Accessed 30 April 2022]

- ↑ The Guardian. 2021. Facebook announces name change to Meta in rebranding effort. [online] Available at: <https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2021/oct/28/facebook-name-change-rebrand-meta> [Accessed 30 April 2022]

- ↑ Srnicek, N., 2020. Platform capitalism. Cambridge: Polity.

- ↑ Heidegger, M. and Stambaugh, J., 1927. On time and being.

- ↑ The Guardian. (2009). Iranian government blocks Facebook access. Retrieved April 28, 2022, from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2009/may/24/facebook-banned-iran

- ↑ Alaa Abdel-Moneim, M., & J. Simon, R. (2009). The Uighur Riots in China: What do Facebook groups say? Retrieved April 26, 2022, from https://www.bpastudies.org/index.php/bpastudies/article/view/108/215

- ↑ State Council. (2000). Measures for the Administration of Internet Information Services (Chinese Text and CECC Partial Translation). Retrieved April 27, 2022, from https://www.cecc.gov/resources/legal-provisions/measures-for-the-administration-of-internet-information-services-cecc

- ↑ TechCrunch. (2022, April 27). China Blocks Access to Twitter, Facebook After Riots. Retrieved from TechCrunch: https://techcrunch.com/2009/07/07/china-blocks-access-to-twitter-facebook-after-riots/?guccounter=1&guce_referrer=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuaW52ZXN0b3BlZGlhLmNvbS9hcnRpY2xlcy9pbnZlc3RpbmcvMDQyOTE1L3doeS1mYWNlYm9vay1iYW5uZWQtY2hpbmEuYXNw&guce_referrer_sig=AQAAAGmgb_

- ↑ The Associated Press. (2016). North Korea officially blocks Facebook, Twitter and YouTube. Retrieved April 28, 2022, from https://mashable.com/article/north-korea-blocks-facebook-twitter

- ↑ Deutsche Welle. (2022). Russia bans 'extremist' Facebook and Instagram. Retrieved April 28, 2022, from https://www.dw.com/en/russia-bans-extremist-facebook-and-instagram/a-61203007

- ↑ Kalyanpur, N., & Newman, A. L. (2019). The MNC-Coalition Paradox: Issue Salience, Foreign Firms and the General Data Protection Regulation*. Journal of Common Market Studies, 57(3), 448–467.

- ↑ Strauss, M., Evdokimova, O., & Semenova, J. (2021). Margrethe Vestager: EU antitrust czar and Big Tech's fiercest opponent. Retrieved March 15, 2022, from https://www.dw.com/en/margrethe-vestager-eu-antitrust-czar-and-big-techs-fiercest-opponent/a-56995791

- ↑ Bernd Oswald. (2022). Digital Services Act - So reguliert die EU künftig Facebook & Co. Retrieved April 29, 2022, from https://www.br.de/nachrichten/netzwelt/digital-services-act-so-reguliert-die-eu-kuenftig-facebook-and-co,T41KlFw

- ↑ European Commission . (2022). The Digital Services Act package. Retrieved April 29, 2022, from https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/digital-services-act-package

- ↑ Associated Press (2019): Facebook plans its own currency for 2 billion-plus users. https://www.deseret.com/2019/6/18/20675911/facebook-plans-its-own-currency-for-2-billion-plus-users#this-undated-image-provided-by-calibra-shows-what-the-calibra-digital-wallet-app-might-look-like-facebook-formed-the-calibra-subsidiary-to-create-a-new-digital-currency-similar-to-bitcoin-for-global-use-one-that-could-drive-more-e-commerce-on-its-services-and-boost-ads-on-its-platforms-facebook-unveiled-the-ambitious-plan-tuesday-june-18-2019-calibra-via-ap

- ↑ Mark Zuckerberg (2019): Facebook post: https://www.facebook.com/zuck/posts/10107693323579671

- ↑ Deyan G. (2022): Facebook’s Cryptocurrency [Libra Explained] https://techjury.net/blog/facebook-cryptocurrency/

- ↑ Reuters (2022): Facebook's cryptocurrency venture to wind down and sell tech assets – WSJ. https://finance.yahoo.com/news/facebooks-cryptocurrency-venture-wind-down-063107953.html?guccounter=1&guce_referrer=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZGVzZXJldC5jb20v&guce_referrer_sig=AQAAADxiEcbulFn6hSQKl-OD7PIMu0lpgw2RPFEQR9uZ-sQexSycglDW4ilGMiKj7KEnEzHmAkL-tA0BIQ69xpG09oJZ63w4VGWqYyrlqmHtgA7WgYl8V7lTXKcP6kKAk0nsZ1Lim8IFYtl_HcSqkVUmLd-dFq-hwpwRxbIUYcM62KbT

- ↑ Peter Rudegeair (2022): Facebook’s Cryptocurrency Venture to Wind Down, Sell Assets https://www.wsj.com/articles/facebooks-cryptocurrency-venture-to-wind-down-sell-assets-11643248799

- ↑ Herb Scribner (2022): Facebook is slowing down its cryptocurrency venture. https://www.deseret.com/2022/1/27/22904451/facebook-cryptocurrency-assets-whats-happening

- ↑ Associated Press (2019): Facebook plans its own currency for 2 billion-plus users. https://www.deseret.com/2019/6/18/20675911/facebook-plans-its-own-currency-for-2-billion-plus-users#this-undated-image-provided-by-calibra-shows-what-the-calibra-digital-wallet-app-might-look-like-facebook-formed-the-calibra-subsidiary-to-create-a-new-digital-currency-similar-to-bitcoin-for-global-use-one-that-could-drive-more-e-commerce-on-its-services-and-boost-ads-on-its-platforms-facebook-unveiled-the-ambitious-plan-tuesday-june-18-2019-calibra-via-ap

- ↑ Deyan G. (2022): Facebook’s Cryptocurrency [Libra Explained] https://techjury.net/blog/facebook-cryptocurrency/

- ↑ United States Senate (2019): Letter to Mark Zuckerberg. https://www.banking.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/5.9.19%20Facebook%20Letter.pdf

- ↑ BBC (2021): Facebook sued for 'losing control' of users’ data. https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-55998588

- ↑ CBI (2019): How Anonymous Is Cryptocurrency? https://cbisecure.com/insights/how-anonymous-is-cryptocurrency/