Category:I703 Python: Difference between revisions

| (107 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

General | =General= | ||

The Python Course is 4 ECTS | The Python Course is 4 ECTS | ||

| Line 8: | Line 7: | ||

E-mail: lauri [donut] vosandi [plus] i703 [ät] gmail [dotchka] com | E-mail: lauri [donut] vosandi [plus] i703 [ät] gmail [dotchka] com | ||

[https://echo360.e-ope.ee/ess/portal/section/1264bfc8-74bf-4926-a816-f1903e372345 Lecture recordings] | |||

==General== | |||

General | |||

* This is not a course for slacking off | * This is not a course for slacking off | ||

| Line 23: | Line 17: | ||

** Networking fundamentals: UDP/TCP ports, logical/hardware address, hostname, domain | ** Networking fundamentals: UDP/TCP ports, logical/hardware address, hostname, domain | ||

** Get along on the command line: cp, mv, mkdir, cd, ssh user@host, scp file user@host: | ** Get along on the command line: cp, mv, mkdir, cd, ssh user@host, scp file user@host: | ||

* (Learn how to) use Google, I am not your tech support | * (Learn how to) use Google, I am not your tech support | ||

* Of course I am there if you're stuck with some corner case or have issues understanding some concepts :) | * Of course I am there if you're stuck with some corner case or have issues understanding some concepts :) | ||

| Line 37: | Line 24: | ||

* If you need more practicing attend CodeClub at Mektory on Wednesdays 18:00, they usually have different exercise every week for beginners | * If you need more practicing attend CodeClub at Mektory on Wednesdays 18:00, they usually have different exercise every week for beginners | ||

* If it looks like there is not much Python programming in this course then that sounds like a good conclusion - that's how Python mainly is used in real life, to glue different components together so they would bring additional value. Don't be afraid to learn other technologies ;) | * If it looks like there is not much Python programming in this course then that sounds like a good conclusion - that's how Python mainly is used in real life, to glue different components together so they would bring additional value. Don't be afraid to learn other technologies ;) | ||

* Learn how to use various [https://pyformat.info/ string formatting] facilities of Python | |||

* Observe Python coding conventions as specified in [https://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0008/ PEP-8] | |||

==Grading== | |||

As this is elective course there is no grade for this course, it's either pass or fail. There are basically two options for passing the course: | |||

Lectures/workshops | * Pick a project down below or propose your own idea and work on it throughout the semester | ||

** Progress visible in Git at least throughout the second half-semester | |||

** Come for a demo in the labs in May. | |||

** Questions will be asked about the code | |||

** You'll be asked to change the behaviour of your software | |||

** If everything checks out fine you've passed the course | |||

* Take an exam on 26th or 27th of May, the exam consists of: | |||

** Bunch of input files | |||

** Description of expected output | |||

** Snippets how to use suggested Python modules | |||

** Your task is to glue it together and make sure it works | |||

==Lectures/workshops== | |||

We'll have something for the first half of semester so you would be able to write | We'll have something for the first half of semester so you would be able to write | ||

| Line 62: | Line 66: | ||

=Lectures/labs= | =Lectures/labs= | ||

==Lecture/lab #1== | ==Lecture/lab #1: file manipulation== | ||

In this lecture/lab we are going to see how we can parse Apache web server log files. These log files contain information about each HTTP request that was made against the web server. Get the example input file [http://enos.itcollege.ee/~lvosandi/access.log here] and check out how the file format looks like. If you are working remotely on enos.itcollege.ee you can simply refer to /var/log/apache2/access.log | In this lecture/lab we are going to see how we can parse Apache web server log files. These log files contain information about each HTTP request that was made against the web server. Get the example input file [http://enos.itcollege.ee/~lvosandi/access.log here] and check out how the file format looks like. If you are working remotely on enos.itcollege.ee you can simply refer to /var/log/apache2/access.log | ||

Easily readable version: | Easily readable version: | ||

| Line 134: | Line 136: | ||

** Use [https://docs.python.org/2/library/urllib.html urllib.unquote] to normalize paths. | ** Use [https://docs.python.org/2/library/urllib.html urllib.unquote] to normalize paths. | ||

==Lecture/lab #2== | ==Lecture/lab #2: directory listing and gzip compression== | ||

So far we've dealed with only one file, usually you're digging through many files and you'd like to automate your work as much as possible. | So far we've dealed with only one file, usually you're digging through many files and you'd like to automate your work as much as possible. | ||

| Line 181: | Line 182: | ||

print line | print line | ||

</source> | </source> | ||

Combine what you've learned so far to parse all access.log and access.log.*.gz files under /var/log/apache2. | |||

Set up Git, you'll have to do this on every machine you use: | Set up Git, you'll have to do this on every machine you use: | ||

<source lang="bash"> | <source lang="bash"> | ||

echo | ssh-keygen -C '' -P '' | |||

git config --global user.name "$(getent passwd $USER | cut -d ":" -f 5)" | git config --global user.name "$(getent passwd $USER | cut -d ":" -f 5)" | ||

git config --global user.email $USER@itcollege.ee | git config --global user.email $USER@itcollege.ee | ||

| Line 200: | Line 204: | ||

</source> | </source> | ||

Also create .gitignore file | Also create .gitignore file and upload the changes. | ||

See [https://github.com/laurivosandi/yet-another-log-parser/ example repository here]. | |||

Exercises: | Exercises: | ||

* Add extra functionality: | * Add extra functionality: | ||

** Create humanize() function which takes number of bytes as input and returns human readable string (eg 8192 bytes becomes 8kB and 5242880 becomes 5MB) | |||

** Use [https://docs.python.org/2/howto/argparse.html argparse] to supply directory path during script invocation and make your program configurable. | |||

==Lecture/lab #3: Parsing command-line arguments== | |||

Use following to parse the command-line arguments: | |||

<source lang="python"> | |||

import argparse | |||

parser = argparse.ArgumentParser(description='Apache2 log parser.') | |||

parser.add_argument('--path', | |||

help="Path to Apache2 log files", default="/var/log/apache2") | |||

parser.add_argument('--verbose', | |||

help="Increase verbosity", action="store_true") | |||

args = parser.parse_args() | |||

print "Log files are expected to be in", args.path | |||

print "Am I going to be extra chatty?", args.verbose | |||

</source> | |||

Now invoke the program with default arguments as following: | |||

<source lang="bash"> | |||

python path/to/example.py | |||

</source> | |||

Program can be invoked with user supplied parameters as following: | |||

<source lang="bash"> | |||

python path/to/example.py --path ~/logs --verbose | |||

</source> | |||

Use following to humanize file sizes/transferred bytes, try to make it shorter! | |||

<source lang="python"> | |||

def humanize(bytes): | |||

if bytes < 1024: | |||

return "%d B" % bytes | |||

elif bytes < 1024 ** 2: | |||

return "%.1f kB" % (bytes / 1024.0) | |||

elif bytes < 1024 ** 3: | |||

return "%.1f MB" % (bytes / 1024.0 ** 2) | |||

else: | |||

return "%.1f GB" % (bytes / 1024.0 ** 3) | |||

</source> | |||

Use datetime to manipulate date/time information, example here: | |||

<source lang="python"> | |||

import os | |||

from datetime import datetime | |||

files = [] | |||

for filename in os.listdir("."): | |||

mode, inode, device, nlink, uid, gid, size, atime, mtime, ctime = os.stat(filename) | |||

files.append((filename, datetime.fromtimestamp(mtime), size)) # Append 3-tuple to list | |||

files.sort(key = lambda(filename, dt, size):dt) | |||

for filename, dt, size in files: | |||

print filename, dt, humanize(size) | |||

print "Newest file is:", files[-1][0] | |||

print "Oldest file is:", files[0][0] | |||

</source> | |||

Exercises: | |||

* Add functionality to our log parser: | |||

** What is the timespan (from-to timestamp) for the results? Use [https://docs.python.org/2/library/datetime.html datetime.strptime] to parse the timestamps from log files. | |||

** Add support for [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Common_Log_Format Common Log Format]. | |||

** What were the most erroneous URL-s? Hint: Use the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_HTTP_status_codes HTTP status code] to determine if there was an error or not. | ** What were the most erroneous URL-s? Hint: Use the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_HTTP_status_codes HTTP status code] to determine if there was an error or not. | ||

** What were the operating systems used to visit the URL-s? | ** What were the operating systems used to visit the URL-s? | ||

** What were the top 5 Firefox versions used to visit the URL-s? | ** What were the top 5 Firefox versions used to visit the URL-s? | ||

** What were the top 5 [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HTTP_referer referrers]? Their [https://docs.python.org/2/library/urlparse.html hostnames]? | ** What were the top 5 [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HTTP_referer referrers]? Their [https://docs.python.org/2/library/urlparse.html hostnames]? | ||

* Advanced: | * Advanced: | ||

** How many requests are coming from local subnets? Hint: IP addresses starting with 192.168. and 172. belong to local network. Use [https://pypi.python.org/pypi/ipaddr ipaddr] to wrap the address, on Python3 it's already bundled | ** How many requests are coming from local subnets? Hint: IP addresses starting with 192.168. and 172. belong to local network. Use [https://pypi.python.org/pypi/ipaddr ipaddr] to wrap the address, on Python3 it's already bundled | ||

** From which countries are the requests coming from? Hint: Use [https://pypi.python.org/pypi/geoip2 GeoIP] to resolve IP addresses to countries. | ** From which countries are the requests coming from? Hint: Use [https://pypi.python.org/pypi/geoip2 GeoIP] to resolve IP addresses to countries. | ||

==Lecture/lab #4: GeoIP lookup and SVG images== | |||

This time we'll try to make some sense out of IP addresses found in the log file. | |||

In case of a personal Ubuntu machine install additional modules for Python 2.x: | |||

<source lang="bash"> | |||

apt-get install python-geoip python-ipaddr python-cssselect | |||

</source> | |||

For Python 3.x on Ubuntu: | |||

<source lang="bash"> | |||

apt-get install python3-geoip python3-ipaddr | |||

</source> | |||

For Mac you can try: | |||

<source lang="bash"> | |||

pip install geoip ipaddr lxml cssselect | |||

</source> | |||

On Ubuntu you can install GeoIP database as a package, but note that it might be out of date: | |||

<source lang="bash"> | |||

sudo apt-get install geoip-database # This places the database under /usr/share/GeoIP/GeoIP.dat | |||

</source> | |||

To get up to date database or to download it for Mac: | |||

<source lang="bash"> | |||

wget http://geolite.maxmind.com/download/geoip/database/GeoLiteCountry/GeoIP.dat.gz | |||

gunzip GeoIP.dat.gz | |||

</source> | |||

Run example: | |||

<source lang="python"> | |||

import GeoIP | |||

gi = GeoIP.open("/usr/share/GeoIP/GeoIP.dat", GeoIP.GEOIP_MEMORY_CACHE) | |||

print "Gotcha:", gi.country_code_by_addr("194.126.115.18").lower() | |||

</source> | |||

Download world map in SVG format: | |||

<source lang="bash"> | |||

wget https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/03/BlankMap-World6.svg | |||

</source> | |||

SVG is essentially a XML-based language for describing [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vector_graphics vector graphics], | |||

hence you can use standard XML parsing tools to modify such file. | |||

Use lxml to highlight a country in the map and save modified file: | |||

<source lang="python"> | |||

from lxml import etree | |||

from lxml.cssselect import CSSSelector | |||

document = etree.parse(open('BlankMap-World6.svg')) | |||

sel = CSSSelector("#ee") | |||

for j in sel(document): | |||

j.set("style", "fill:red") | |||

# Remove styling from children | |||

for i in j.iterfind("{http://www.w3.org/2000/svg}path"): | |||

i.attrib.pop("class", "") | |||

with open("highlighted.svg", "w") as fh: | |||

fh.write(etree.tostring(document)) | |||

</source> | |||

Exercises: | |||

* Add GeoIP lookup to your log parser | |||

* Highlight countries on the world map | |||

* Use [http://www.w3schools.com/cssref/css_colors_legal.asp HSL color codes] to make your life easier | |||

* Commit changes to your Git repository, but do NOT include the GeoIP database in your program source | |||

==Lecture/lab #5: Jinja templating engine== | |||

In this lab we take a look how we can use Jinja templating engine to output HTML. | |||

In case of a personal Ubuntu machine install additional modules for Python 2.x: | |||

<source lang="bash"> | |||

apt-get install python-jinja2 | |||

</source> | |||

For Python 3.x on Ubuntu: | |||

<source lang="bash"> | |||

apt-get install python3-jinja2 | |||

</source> | |||

For Mac you can try: | |||

<source lang="bash"> | |||

pip install jinja2 | |||

</source> | |||

The template placed in report.html next to main.py: | |||

<source lang="html5"> | |||

<!DOCTYPE html> | |||

<html> | |||

<head> | |||

<meta charset="utf-8"/> | |||

<title>Out awesome report</title> | |||

<link rel="css/style.css" type="text/css"/> | |||

<script type="text/javascript" src="js/main.js"></script> | |||

</head> | |||

<body> | |||

<h1>Top bandwidth hoggers</h1> | |||

<ul> | |||

{% for user, bytes in user_bytes[:5] %} | |||

<li>{{ user }}: {{ humanize(bytes) }}</li> | |||

{% endfor %} | |||

</ul> | |||

<h1>Visits per country</h1> | |||

<img src="highlighted.svg"/> | |||

</body> | |||

</html> | |||

</source> | |||

The Python snippet for generating output.html from report.html: | |||

<source lang="python"> | |||

user_bytes = sorted(user_bytes.items(), key = lambda item:item[1], reverse=True) | |||

from jinja2 import Environment, FileSystemLoader # This it the templating engine we will use | |||

env = Environment( | |||

loader=FileSystemLoader(os.path.dirname(__file__)), | |||

trim_blocks=True) | |||

import codecs | |||

with codecs.open("output.html", "w", encoding="utf-8") as fh: | |||

fh.write(env.get_template("report.html").render(locals())) | |||

# locals() is a dict which contains all locally defined variables ;) | |||

os.system("x-www-browser file://" + os.path.realpath("output.html") + " &") | |||

</source> | |||

A very lazy way of using single template file with Jinja2: | |||

<source lang="python"> | |||

import codecs | |||

from jinja2 import Template | |||

template = Template(open("path/to/template.html").read()) | |||

ctx = { | |||

"filenames": os.listdir("path/to/input/directory") | |||

} | |||

with codecs.open("path/to/index.html", "w", encoding="utf-8") as fh: | |||

fh.write(template.render(ctx)) | |||

</source> | |||

Exercises: | |||

* Organise your map and HTML template under [https://github.com/laurivosandi/yet-another-log-parser/tree/master/templates templates/ directory] in the source code tree | |||

* Add command-line argument for specifying the output directory which defaults to build/ in current directory | |||

* [https://docs.python.org/2/library/os.html#os.makedirs Create the output directory] if necessary | |||

==Lecture/lab #6: Flask web development framework== | |||

Following should give a general idea how the Flask works: | |||

<source lang="python"> | |||

# Stuff's missing here of course! | |||

from flask import Flask, request | |||

app = Flask(__name__) | |||

def list_log_files(): | |||

""" | |||

This is simply used to filter the files in the logs directory | |||

""" | |||

for filename in os.listdir("/var/log/apache2"): | |||

if filename.startswith("access"): | |||

yield filename | |||

@app.route("/report/") | |||

def report(): | |||

# Create LogParser instance for this report | |||

logparser = LogParser(gi, KEYWORDS) | |||

filename = request.args.get("filename") | |||

if "/" in filename: # Prevent directory traversal attacks | |||

return "Go away!" | |||

path = os.path.join("/var/log/apache2", filename) | |||

logparser.parse_file(gzip.open(path) if path.endswith(".gz") else open(path)) | |||

return env.get_template("report.html").render({ | |||

"map_svg": render_map(open(os.path.join(PROJECT_ROOT, "templates", "map.svg")), logparser.countries), | |||

"humanize": humanize.naturalsize, | |||

"keyword_hits": sorted(logparser.d.items(), key=lambda i:i[1], reverse=True), | |||

"url_hits": sorted(logparser.urls.items(), key=lambda i:i[1], reverse=True), | |||

"user_bytes": sorted(logparser.user_bytes.items(), key = lambda item:item[1], reverse=True) | |||

}) | |||

@app.route("/") | |||

def index(): | |||

return env.get_template("index.html").render( | |||

log_files=list_log_files()) | |||

if __name__ == '__main__': | |||

app.run(debug=True) | |||

</source> | |||

==Lecture/lab #7: image manipulation and threading== | |||

[http://www.pythonware.com/products/pil/ Python imaging library] is a module for manipulating bitmap images with Python. | |||

On Ubuntu you can install it with: | |||

<source lang="bash"> | |||

sudo apt-get install python-pil | |||

</source> | |||

On Mac and Ubuntu: | |||

<source lang="bash"> | |||

pip install pillow | |||

</source> | |||

Let's say you've travelled abroad and taken a lot of photos with high resolution. It would take ages to upload the images to your favourite website for showing off to your friends. Manually resizing each image is also tedious. You can use Python to write a script for resizing the images automatically. Here is a single-threaded version: | |||

<source lang="python"> | |||

import os | |||

from PIL import Image | |||

d = "/home/lvosandi/images" | |||

output = os.path.join(d, "smaller") | |||

if not os.path.exists(output): | |||

os.makedirs(output) | |||

for filename in os.listdir(d): | |||

if not filename.lower().endswith(".jpg"): | |||

continue | |||

im = Image.open(os.path.join(d, filename)) | |||

width, height = im.size | |||

smaller = im.resize((320, height * 320 / width)) | |||

smaller.save(os.path.join(output, filename)) | |||

</source> | |||

Nowadays most processors incorporate many cores onto the same chip, most programming languages however don't support very well taking advantage of such hardware. [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thread_%28computing%29 Threads] are one option for making use of multiple cores. | |||

We can speed up the resizing by using multiple threads, your milage will vary depending on how many cores your computer has and how fast your permanent storage is. Multi-threaded version of the program above would look something like this: | |||

<source lang="python"> | |||

import os | |||

from threading import Thread | |||

from PIL import Image | |||

d = "/home/lvosandi/images" # This is the input folder | |||

output = os.path.join(d, "smaller") # This is the output folder for small images | |||

filenames = os.listdir(d) # This is the list of files in the input folder | |||

class ImageConverter(Thread): # ImageConverter shall be subclass of Thread | |||

def run(self): # It has run function which is run in a separate thread | |||

while True: | |||

try: | |||

filename = filenames.pop() # Try to get a filename from the list | |||

except IndexError: | |||

break | |||

if not filename.lower().endswith(".jpg"): | |||

continue | |||

print self.getName(), "is processing", filename | |||

im = Image.open(os.path.join(d, filename)) | |||

width, height = im.size | |||

smaller = im.resize((800, height * 800 / width)) | |||

smaller.save(os.path.join(output, filename)) | |||

if not os.path.exists(output): | |||

os.makedirs(output) | |||

threads = [] | |||

for i in range(0, 8): | |||

threads.append(ImageConverter()) | |||

for thread in threads: | |||

thread.start() # Start up the threads | |||

for thread in threads: | |||

thread.join() # Wait them to finish | |||

</source> | |||

On Intel i7-4770R (4 cores/8 threads) you should get something like this with pillow 3.2.0: | |||

[[File:Pillow-multithreading.png]] | |||

We can see that total exection time (real time) drops until we add up to 4 threads without significant increase in CPU time (userspace/kernelspace time). This means the job is distributed along four cores of the machine. Increasing count of threads up to 8 doesn't yeild much improvement in the execution time but CPU time consumption increases most likely because the ALU-s of four cores are shared between eight hardware threads and they have to wait until other thread frees up the ALU. Conclusion: the sweet spot for this kind of workload is 4 threads. | |||

Exercises: | |||

* Add command-line argument parsing with argparse: output directory path and output resolution | |||

* Implement widest edge detection so images can be resized into desired dimensions while preserving aspect ratio | |||

* Implement multithreading for the log parser we've worked on earlier, how much speed up are you gaining? | |||

==Lecture/lab #8: subprocess== | |||

It seems the audio is missing on the lecture recording so here's a short summary what we did: Mohanad had a demo about the sumorobot v2.0 prototype he had been working on; later I explained more the details of Python multithreading - where it makes sense to use and where not. Due to [https://wiki.python.org/moin/GlobalInterpreterLock global interpreter lock] only one thread can make use of CPU intensive Python code. Using Python's multithreading makes mainly sense for networking and I/O (eg. urllib) - where the bottleneck is not CPU. You can use subprocess module to push certain tasks to separate processes, thus avoiding the bottlenecks of global interpreter lock. | |||

An example of pushing gzip decompression to separate process with subprocess module looks like this: | |||

<source lang="python"> | |||

proc = subprocess.Popen(["/bin/zcat", "logs/access.log.1.gz"], | |||

stdout=subprocess.PIPE) | |||

fh = proc.stdout | |||

print fh.readline() | |||

for line in fh: | |||

print line | |||

</source> | |||

==Lecture/lab #9: Regular expressions== | |||

[https://echo360.e-ope.ee/ess/echo/presentation/390b0624-8c9b-4dd9-bd88-fe4a5391457b Lecture recording]. | |||

Regular expressions are used to match arbitrary strings. For example consider text input field in a HTML5 document: | |||

<source lang="html5"> | |||

<input type="text" name="username" pattern="[a-z][a-z0-9]+"/> | |||

</source> | |||

This would allow entering string which starts with lowercase letter and is then followed by one or more alphanumerical characters. The pattern here is an example of regular expression. On command line you'll see regex when dealing with grep, sed and many other tools. You can apply regexes in [http://php.net/manual/en/function.preg-match.php PHP] and use the same patterns for [http://www.w3schools.com/tags/att_input_pattern.asp HTML5] as shown above. | |||

Python as many programming languages supports regular expressions and we can use them to replace our manually crafted code for parsing the data with a single line of code. See [https://docs.python.org/2/howto/regex.html Python documentation for more information about what is supported by the Python's regex flavour]: | |||

<source lang="python"> | |||

import re | |||

RE_LOG_ENTRY = ( | |||

"(\d+\.\d+\.\d+\.\d+) " # Source IPv4 address | |||

"\- " | |||

"(\w+|-) " # Username if authenticated otherwise - | |||

"\[(.+?)\] " # Timestamp between square brackets | |||

"\"([A-Z]+) (/.*?) HTTP/\d\.\d\" " # HTTP request method, path and version | |||

"(\d+) " # Status code | |||

"(\d+) " # Content length in bytes | |||

"\"(.+?)\" " # Referrer between double quotes | |||

"\"(.+?)\"" # User agent between double quotes | |||

) | |||

for line in open("/var/log/apache2/access.log"): | |||

m = re.match(RE_LOG_ENTRY, line) | |||

if not m: | |||

print "Failed to parse:", line | |||

continue | |||

source_ip, remote_user, timestamp, method, path, status_code, content_length, referrer, agent = m.groups() | |||

content_length = int(content_length) # The regex has no clue about the data types, hence we have to cast str to int here | |||

path = urllib.unquote(path) # Also regexes are not aware about charset mess, hence we have to unquote string here | |||

print "Got a hit from", source_ip, "to", path | |||

</source> | |||

In the example above m.groups() returns an array of strings that were extracted by parenthesis. The order of groups has to remain the same for the input files. We can also name the groups in which case the order of groups is no more relevant: | |||

<source lang="python"> | |||

import re | |||

RE_LOG_ENTRY = ( | |||

"(?P<source_ip>\d+\.\d+\.\d+\.\d+) " | |||

"\- " | |||

"(?P<remote_user>\w+|-) " | |||

"\[(?P<timestamp>.+?)\] " | |||

"\"(?P<method>[A-Z]+) (?P<path>/.*?) HTTP/\d\.\d\" " | |||

"(?P<status_code>\d+) " | |||

"(?P<content_length>\d+) " | |||

"\"(?P<referrer>.+?)\" " | |||

"\"(?P<user_agent>.+?)\"" | |||

) | |||

for line in open("/var/log/apache2/access.log"): | |||

m = re.match(RE_LOG_ENTRY, line) | |||

if not m: | |||

print "Failed to parse:", line | |||

continue | |||

print m.groupdict() | |||

</source> | |||

Exercises: | |||

* Modify your log parser and make use of regular expressions | |||

==Lecture/lab #10: data visualization== | |||

Matplotlib is a neat Python package for visualizing data. | |||

Here's an example for charting random generated numbers and viewing the chart with built-in viewer: | |||

<source lang="python"> | |||

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt | |||

import numpy as np | |||

samples = np.random.randint(100, size=50) # List of 50 random numbers within range 0..100 | |||

plt.plot(samples) | |||

plt.show() | |||

</source> | |||

To have an more object-oriented approach, the plt.figure() can be used to fever to figures which could contain multiple plots: | |||

<source lang="python"> | |||

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt | |||

import numpy as np | |||

y1 = np.random.randint(100, size=50) # List of 50 random numbers within range 0..100 | |||

y2 = np.random.randint(100, size=50) # Another list | |||

fig = plt.figure() | |||

sub1 = fig.add_subplot(2, 1, 1) | |||

sub1.plot(y1) | |||

sub2 = fig.add_subplot(2, 1, 2) | |||

sub2.plot(y2) | |||

fig.savefig("test.svg", format="svg") | |||

</source> | |||

Often you find yourself plotting data series, eg how many events happened (HTTP requests) in a certain period (date, week, month). Here's an example for plotting file modification times under /tmp grouped by date: | |||

<source lang="python"> | |||

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt | |||

import numpy as np | |||

import os | |||

from datetime import datetime | |||

from collections import Counter | |||

from matplotlib import rcParams | |||

# Customize fonts | |||

rcParams['font.family'] = 'sans' | |||

rcParams['font.sans-serif'] = ['Gentium'] | |||

# Skim through /tmp | |||

recent_files = Counter() | |||

for root, dirs, files in os.walk("/tmp"): | |||

for filename in files: | |||

mode, inode, device, nlinks, uid, gid, size, atime, mtime, ctime = os.lstat(os.path.join(root, filename)) | |||

recent_files[datetime.utcfromtimestamp(mtime).date()] += 1 | |||

fig = plt.figure( figsize=(10, 5)) | |||

sub1 = fig.add_subplot(1, 1, 1) | |||

sub1.barh(recent_files.keys(), recent_files.values()) | |||

fig.savefig("tmp.svg", format="svg") | |||

</source> | |||

Use following to parse the timestamp string in the log file: | |||

<source lang="bash"> | |||

hist_per_day = Counter() | |||

# ... | |||

hits_per_day[datetime.strptime(timestamp[:-6], "%d/%b/%Y:%H:%M:%S").date()] += 1 | |||

</source> | |||

If you have trouble with month name parsing, try running Python like this: | |||

<source lang="bash"> | |||

LC_TIME= python script.py # This will disable datetime localization | |||

</source> | |||

Exercises: | |||

* Add hits per week charts to the log parser | |||

* Add gigabytes per month charts to the log parser | |||

==Lecture/lab #11: MySQL database interaction== | |||

This time we took a look at database interaction with MySQLdb. | |||

On Ubuntu use following to install MySQL library bindings for Python: | |||

<source lang="bash"> | |||

apt-get install python-mysqldb | |||

</source> | |||

On Mac: | |||

<source lang="bash"> | |||

brew install mysql --client-only --universal | |||

pip install MySQL-python | |||

</source> | |||

Unfortunately this module is not yet available for Python3, but you can use pure-Python implementation instead. | |||

If you want to connect from home, set up SSH port forward and replace 172.168.0.82 with 127.0.0.1 below: | |||

<source lang="bash"> | |||

ssh user@enos.itcollege.ee -L 3306:localhost:3306 | |||

</source> | |||

Example code: | |||

<source lang="python"> | |||

import MySQLdb | |||

import random | |||

SQL_CREATE_TABLES = """ | |||

CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS `another_table` ( | |||

`id` int(11) NOT NULL AUTO_INCREMENT, | |||

`created` timestamp NOT NULL DEFAULT CURRENT_TIMESTAMP, | |||

`ip_address` varchar(15) NOT NULL, | |||

`hits` int(11) NOT NULL, | |||

PRIMARY KEY (`id`) | |||

); | |||

""" | |||

SQL_GET_STUFF = """ | |||

select | |||

* | |||

from | |||

another_table | |||

""" | |||

SQL_INSERT_STUFF = """ | |||

insert into | |||

another_table(ip_address, hits) | |||

values | |||

(%s, %s) | |||

""" | |||

# In school network this should suffice | |||

conn = MySQLdb.connect( | |||

host="172.16.0.82", db="test", user="test", passwd="t3st3r123") | |||

cursor = conn.cursor() | |||

print "Creating tables if necessary" | |||

cursor.execute(SQL_CREATE_TABLES) | |||

cursor.execute(SQL_GET_STUFF) | |||

cols = [j[0] for j in cursor.description] | |||

for row in cursor: | |||

fields = dict(zip(cols, row)) | |||

print "Table row:", fields | |||

# Following basically already does: prepare, bind_param and execute | |||

cursor.execute(SQL_INSERT_STUFF, ("127.0.0.1", random.randint(0,100))) | |||

# This will actually save the data | |||

conn.commit() | |||

</source> | |||

=Photo sanitization tool= | |||

==Parsing EXIF data from photos== | |||

EXIF data is often included in an JPEG image in addition to the image data. | |||

You can parse EXIF data from Linux command line like this: | |||

<source lang="bash"> | |||

exif path/to/filename.jpg | |||

</source> | |||

For Python there is module available as well: | |||

<source lang="bash"> | |||

sudo apt-get install python-exif | |||

</source> | |||

To get GPS coordinates and image orientation: | |||

<source lang="python"> | |||

try: | |||

from exifread import process_file # This is for newer Ubuntus | |||

except ImportError: | |||

from EXIF import process_file # This is for Ubuntu 14.04 | |||

def degrees(j): | |||

return j.values[0].num + (j.values[1].num + j.values[2].den * 1.0 / j.values[2].num) / 60.0 | |||

tags = process_file(open("path/to/filename.jpg")) | |||

lat, lng = tags.get("GPS GPSLatitude"), tags.get("GPS GPSLongitude") | |||

if lat and lng: | |||

print "%.4f,%.4f" % (degrees(lat), degrees(lng)), | |||

# Parse datetime of the photo | |||

timestamp = tags.get("EXIF DateTimeOriginal") | |||

if timestamp: | |||

print timestamp.values, | |||

# Parse image orientation | |||

orientation = tags.get("Image Orientation") | |||

if orientation: | |||

j, = orientation.values | |||

if j == 6: | |||

print "rotated 270 degrees", | |||

elif j == 8: | |||

print "rotated 90 degrees", | |||

elif j == 3: | |||

print "rotated 180 degrees", | |||

print | |||

</source> | |||

==Rotating images== | |||

Here's an example how to rotate images with Python Imaging Library, try it out on bpython shell: | |||

<source lang="python"> | |||

import Image | |||

orig = Image.open("original.jpg") | |||

rotated = orig.transpose(Image.ROTATE_90) # This happens only in the RAM! | |||

rotated.save("rotated.jpg") | |||

</source> | |||

==Specification== | |||

Paranoid Patrick wants to share some files, but he's afraid the photos contain some information that's not intended for sharing. | |||

Also he's reluctant to upload files to Dropbox so he needs minimal user interface to list the images in a directory. | |||

Help him write a Python script that strips EXIF information and generates HTML file which indexes the files. | |||

* GPS coordinate information must be stripped | |||

* Image rotation must be preserved (90, 180, 270 degrees only) | |||

* Use thumbnail size of 192px | |||

Hints: | |||

* Python Imaging Library ignores EXIF tags | |||

Inputs: | |||

* Path to directory which contains the photos specified as command line argument | |||

* Path to the directory where sanitized photos and index.html will be placed | |||

Outputs: | |||

* Sanitized JPEG files using the original filename (path/to/output/directory/blah.jpg) | |||

* Thumbnails of the JPEG files (path/to/output/directory/thumbnails/blah.jpg) | |||

* index.html which shows thumbnails in the listing and has links to the sanitized JPEG files | |||

Example invocation: | |||

<source lang="bash"> | |||

python paranoia.py path/to/input/directory/ path/to/output/directory/ | |||

</source> | |||

Example inputs can be downloaded from here: | |||

<source lang="bash"> | |||

wget http://enos.itcollege.ee/~lvosandi/pics.zip | |||

</source> | |||

Example output can be examined [http://enos.itcollege.ee/~lvosandi/paranoid-output/ here] or downloaded [http://enos.itcollege.ee/~lvosandi/paranoid-output.zip here]. | |||

==Path to the solution== | |||

This will not be included in the test description, but you can remember this as a guideline for solving most of the problems: | |||

1. Create a for loop for iterating over files | |||

2. Add command line parsing with argparse or lazy input_path, output_path = sys.argv[1:] | |||

3. Create output directory for stripped JPEG files | |||

4. In each for iteration of the loop: | |||

4.1. open the original file | |||

4.2. Rotate as necessary | |||

4.3. Save rotated file to output directory | |||

4.4. Save the thumbnail of the image to the output directory | |||

5. Generate index.html using Jinja or simply write to output file line by line throughout the for loop | |||

==Example submission== | |||

Cleaned up and simplified version of what was shown in the end of the lecture: | |||

<source lang="python"> | |||

import codecs, os, sys, EXIF | |||

from PIL import Image | |||

from jinja2 import Template | |||

# Grab arguments specified on the command line after: python paranoia.py <input_dir> <output_dir> | |||

input_directory, output_directory = sys.argv[1:] | |||

# Create output directories if necessary | |||

if not os.path.exists(output_directory): | |||

os.makedirs(os.path.join(output_directory, "thumbnails")) | |||

HEADER = """<!DOCTYPE html> | |||

<html> | |||

<head> | |||

<meta charset="utf-8"/> | |||

<style> | |||

body { background-color: #444; } | |||

img.thumb { position: relative; display: inline; margin: 1em; | |||

padding: 0; width: 192; height: 192; | |||

box-shadow: 0px 0px 10px rgba(0,0,0,1); } | |||

</style> | |||

</head> | |||

<body> | |||

""" | |||

# Open index.html in output diretory and write it line by line | |||

with open(os.path.join(output_directory, "index.html"), "w") as fh: | |||

fh.write(HEADER) | |||

for filename in os.listdir(input_directory): | |||

# Read EXIF tags | |||

tags = EXIF.process_file(open(os.path.join(input_directory, filename))) | |||

# Read image data | |||

original = Image.open(os.path.join(input_directory, filename)) | |||

# Rotate as necessary | |||

rotated = original # Not rotated at all | |||

orientation = tags.get("Image Orientation") # Parse image orientation | |||

if orientation: | |||

j, = orientation.values | |||

if j == 6: | |||

rotated = original.transpose(Image.ROTATE_270) | |||

elif j == 8: | |||

rotated = original.transpose(Image.ROTATE_90) | |||

elif j == 3: | |||

rotated = original.transpose(Image.ROTATE_180) | |||

rotated.save(os.path.join(output_directory, filename)) | |||

# Save thumbnail | |||

rotated.thumbnail((192,192), Image.ANTIALIAS) | |||

rotated.save(os.path.join(output_directory, "thumbnails", filename)) | |||

fh.write(""" <a href="%s">""" % filename) | |||

fh.write("""<img class="thumb" src="thumbnails/%s"/>""" % filename) | |||

fh.write("""</a>\n""") | |||

fh.write(" </body>\n") | |||

fh.write("</html>\n") | |||

</source> | |||

=Music collection disaster recovery tool= | |||

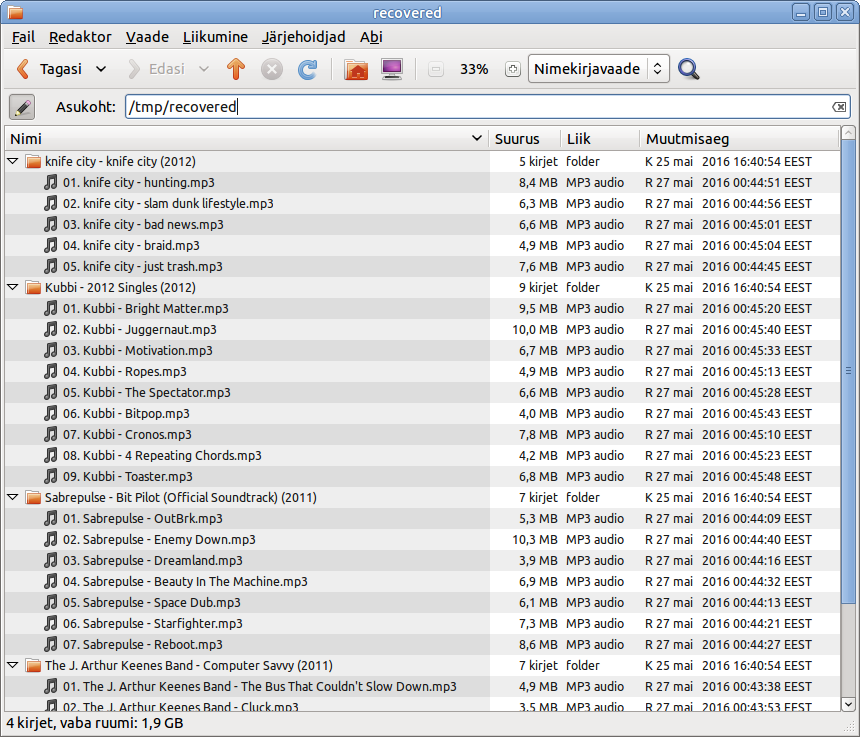

==Background== | |||

Unlucky Bob accidentally formatted the SD card on his smartphone. He managed to recover most of the files using disaster recovery tools, but the filenames are still messed up. | |||

Help Bob write a script that restores the filenames of his music collection. | |||

* Use ID3 tags to determine artist name, album name and track title of a MP3 file | |||

* Group album tracks into same directories: <artist name> - <album name> (<year>) | |||

* Use consistent naming for filenames: <track number>. <artist name> - <track title> | |||

* Final filenames must be sortable by track number (hint: other observe that track numbers are padded to two digits) | |||

==Invocation== | |||

Example input files are available as a Zip archive from http://upload.itcollege.ee/python/mess.zip: | |||

<source lang="bash"> | |||

wget http://upload.itcollege.ee/python/mess.zip | |||

unzip -d /tmp/ mess.zip | |||

</source> | |||

Example of program invocation: | |||

<source lang="bash"> | |||

python recover.py /tmp/mess/ /tmp/recovered/ | |||

</source> | |||

You open up the directories in the file browser like this: | |||

<source lang="bash"> | |||

nautilus /tmp/mess/ /tmp/recovered/ & | |||

</source> | |||

==Hints== | |||

Based on first bytes of a file also known as magic bytes we can *usually* determine the file type using `magic` module: | |||

<source lang="python"> | |||

import magic | |||

db = magic.open(magic.MAGIC_MIME_TYPE) | |||

db.load() # Loads the magic bytes database | |||

print "MIME type of the file is:", db.file("filename.here") | |||

</source> | |||

Additionally MP3 tracks have metadata information bundled which contain the artist, album and track name of a file. We can use `mutagen` module to parse ID3 tags from an MP3 track: | |||

<source lang="python"> | |||

from mutagen.easyid3 import EasyID3 | |||

from mutagen.id3 import ID3NoHeaderError | |||

try: | |||

tags = EasyID3("probably-mp3-file.mp3") | |||

except ID3NoHeaderError: | |||

print "No ID3 tags present" | |||

else: | |||

print tags | |||

</source> | |||

To make a directory: | |||

<source lang="python"> | |||

import os | |||

if not os.path.exists("path/to/destination"): os.makedirs("path/to/destination") | |||

</source> | |||

To copy a file: | |||

<source lang="python"> | |||

import shutil | |||

shutil.copy("path/to/source/0000001", "path/to/destination/filename.mp3") | |||

</source> | |||

==Grading== | |||

Points start from 100 and every mistake will make you lose some points: | |||

* Ask for an extra hint from the supervisor (-15p) | |||

* Incomplete or no command-line argument parsing (-15p) | |||

* Final filenames are not sortable (-15p) | |||

* Some files which are definitely MP3-s are not processed (-15p) | |||

* Program crashes with provided example files (-30p) | |||

* Program crashes with another set of files (-10p) | |||

* File path format is not <output directory>/<artist name> - <album name> (<year>)/<track number>. <artist name> - <track title>.mp3 (-15p) | |||

Example output path for an MP3 track would look something like: | |||

/tmp/recovered/The J. Arthur Keenes Band - Computer Savvy (2011)/02. The J. Arthur Keenes Band - Cluck.mp3 | |||

Course is passed if you manage to lose no more than 50 points. | |||

==Example submission== | |||

<source lang="python"> | |||

import shutil, sys, magic, os | |||

from mutagen.easyid3 import EasyID3 | |||

from mutagen.id3 import ID3NoHeaderError | |||

db = magic.open(magic.MAGIC_MIME_TYPE) | |||

db.load() # Loads the magic bytes database | |||

try: | |||

input_directory, output_directory = sys.argv[1:3] | |||

except ValueError: | |||

print "Not enough arguments!" | |||

sys.exit(255) | |||

for filename in os.listdir(input_directory): | |||

# Concatenate the absolute directory path to relative filename | |||

path = os.path.join(input_directory, filename) | |||

if db.file(path) not in ("application/octet-stream", "audio/mpeg"): | |||

# Skip images, PDF-s and other files which definitely don't have ID3 tags | |||

continue | |||

try: | |||

tags = EasyID3(path) | |||

except ID3NoHeaderError: | |||

# Skip file if the file didn't contain ID3 tags | |||

continue | |||

artist, = tags.get("artist") # Same as: artist = tags.get("artist")[0] | |||

album, = tags.get("album") | |||

title, = tags.get("title") | |||

year, = tags.get("date") | |||

tracknumber, = tags.get("tracknumber") | |||

if "/" in tracknumber: # Handle 3/5 (track number / total number of tracks) | |||

tracknumber, _ = tracknumber.split("/") | |||

# Generate directory name and target filename | |||

directory_name = "%s - %s (%s)" % (artist, album, year) | |||

target_name = "%02d. %s - %s.mp3" % (int(tracknumber), artist, title) | |||

# Create directory for album if necessary | |||

if not os.path.exists(os.path.join(output_directory, directory_name)): | |||

os.makedirs(os.path.join(output_directory, directory_name)) | |||

# Copy the file to directory with new filename | |||

shutil.copy( | |||

path, | |||

os.path.join(output_directory, directory_name, target_name)) | |||

print "Move from:", filename, "to:", os.path.join(directory_name, target_name) | |||

</source> | |||

Outcome: | |||

[[File:Recovered-screenshot.png]] | |||

=Video transcoding tool= | |||

==Background== | |||

Nowadays the web browser are capable of playing back video without additional plugins. As a content publisher you just have to make it sure that the videos are available in supported formats. | |||

Unfortunately widely used h264 video encoding is covered with patents and could not become part of an open standard such as HTML. Hence in countries where software patents are enforced such as USA - Mozilla and Google are using alternative codecs to enable video playback in a web browser. Mozilla Firefox relies on royality-free Theora video codec and Vorbis audio codec in a OGG container. For older releases of Google Chrome you need to use VP8 video and Vorbis audio in WebM container. For other browsers h264 video codec and AAC audio codec stored in MP4 container should suffice. | |||

Implement a Python script that can be used as Poor Man's Youtube - script which iterates over files in a directory specified as command-line argument and in the output directory generates: | |||

* Video files suitable for Google Chrome (<output directory>/transcode/<output filename>.webm) | |||

* Video files suitable for Mozilla Firefox (<output directory>/transcode/<output filename>.ogv) | |||

* Video files suitable for other browsers (<output directory>/transcode/<output filename>.mp4) | |||

* JPEG thumbnails of the videos (<output directory>/thumbs/<output filename>.jpg) | |||

* HTML page which lists the videos and enables playback (<output directory>/index.html) | |||

==Example invocation== | |||

To run the script: | |||

<source lang="bash"> | |||

python transcode.py <input directory> <output directory> | |||

</source> | |||

The script should create output directory if necessary. The script should only attempt to convert recognized video files in the input directory, that is files whose mimetype begins with video/ or alternatively you can just check if filename ends with .avi, .mov, .ogv, .webm, .mp4, .mpg or .flv. | |||

==Hints== | |||

FFMPEG is a neat software which supports plenty of video formats and you can use it on command-line to convert almost any video file to the formats mentioned above: | |||

<source lang="bash"> | |||

avconv -i input.any -vcodec libx264 -acodec aac -strict experimental -y output.mp4 | |||

avconv -i input.any -vcodec libtheora -acodec libvorbis -y output.ogv | |||

avconv -i input.any -vcodec libvpx -acodec libvorbis -y output.webm | |||

</source> | |||

To extract a frame as JPEG to be used as thumbnail: | |||

<source lang="bash"> | |||

avconv -ss 3 -i input.any -vframes 1 -y thumbs/output.jpg | |||

</source> | |||

To invoke programs from Python use 'os.system': | |||

<source lang="python"> | |||

import os | |||

os.system("avconv -i " + input_path + " ... -y " + output_path) | |||

</source> | |||

To extract bits from the path use 'os.path.basename' and 'os.path.splitext': | |||

<source lang="python"> | |||

import os | |||

filename = os.path.basename("path/to/some-videofile.avi") | |||

print filename # some-videofile.avi | |||

name, extension = os.path.splitext(filename) | |||

print name # some-videofile | |||

print extension # .avi | |||

</source> | |||

To create directories: | |||

<source lang="python"> | |||

if not os.path.exists("transcode"): | |||

os.makedirs("transcode") | |||

</source> | |||

To determine mime type based on file extension you can use mimetypes module, it should detect *all* video file extensions: | |||

<source lang="python"> | |||

import mimetypes | |||

content_type, content_encoding = mimetypes.guess_type("somefile.avi") | |||

print content_type # video/x-msvideo | |||

content_type, content_encoding = mimetypes.guess_type("otherfile.mpg") | |||

print content_type # video/mpeg | |||

</source> | |||

==Get some video clips== | |||

The main problem of uploading videos to web is that the videos are generated by variety of software and use diverse set of audio and video codecs: | |||

<source lang="bash"> | |||

wget http://download.blender.org/demo/movies/ChairDivXL.avi | |||

wget http://download.blender.org/demo/movies/Plumiferos_persecucion_casting.mpg | |||

wget http://download.blender.org/demo/movies/elephantsdream_teaser.mp4 | |||

wget http://video.blendertestbuilds.de/download.blender.org/peach/trailer_480p.mov | |||

</source> | |||

==Example HTML== | |||

Use jinja2 or just `fh = open(...); fh.write(...)` to generate HTML: | |||

<source lang="html5"> | |||

<!DOCTYPE html> | |||

<html> | |||

<head> | |||

<meta charset="utf-8"/> | |||

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, user-scalable=no"/> | |||

</head> | |||

<body> | |||

<h>example-video</h> | |||

<video poster="thumbs/example-video.jpg" controls> | |||

<source src="transcode/example-video.ogv" type="video/ogg"> | |||

<source src="transcode/example-video.mp4" type="video/mp4"> | |||

<source src="transcode/example-video.webm" type="video/webm"> | |||

</video> | |||

<!-- Other videos go here --> | |||

</body> | |||

</html> | |||

</source> | |||

==Example submission== | |||

<source lang="python"> | |||

import mimetypes, sys, os | |||

profiles = ( | |||

("-vcodec libx264 -acodec aac -strict experimental", "mp4", "video/mp4"), | |||

("-vcodec libtheora -acodec libvorbis", "ogv", "video/ogg"), | |||

("-vcodec libtheora -acodec libvorbis", "webm", "video/webm")) | |||

input_dir, output_dir = sys.argv[1:3] | |||

for subdir in "transcode", "thumbs": | |||

if not os.path.exists(os.path.join(output_dir, subdir)): | |||

os.makedirs(os.path.join(output_dir, subdir)) | |||

with open(os.path.join(output_dir, "index.html"), "w") as fh: | |||

fh.write("""<!DOCTYPE><html><head><meta chatset="utf-8"></head><body>""") | |||

for filename in os.listdir(input_dir): | |||

content_type, content_encoding = mimetypes.guess_type(filename) | |||

if not content_typeo or content_type.startswith("video/"): continue | |||

name, extension = os.path.splitext(filename) | |||

fh.write("""<h1>%(name)s</h1><video poster="%(output_dir)s/thumbs/%(name)s.jpg" controls>""" % locals()) | |||

input_path = os.path.join(input_dir, filename) | |||

for codec, ext, content_type in profiles: | |||

fh.write("""<source src="transcode/%(name)s.%(ext)s" type="%(content_type)s"/>""" % locals()) | |||

os.system("avconv -i %(input_path)s %(codec)s -y %(output_dir)s/transcode/%(name)s.%(ext)s" % locals()) | |||

os.system("avconv -i %(input_path)s -vframes 1 -y %(output_dir)s/thumbs/%(name)s.jpg" % locals()) | |||

fh.write("</video>") | |||

fh.write("</body></html>") | |||

</source> | |||

=Project ideas= | =Project ideas= | ||

==/proc/cpuinfo flags parser== | |||

Create a small util for parsing cpuinfo flags, eg does my processor support: hardware assisted virtualization, accelearted AES encryption, etc? | |||

http://unix.stackexchange.com/questions/43539/what-do-the-flags-in-proc-cpuinfo-mean#43540 | |||

==Certificate signing request utility== | |||

Under Windows it's rather painful to generate X509 signing request, see full workflow [https://wiki.itcollege.ee/index.php/Category:I802_Firewalls_and_VPN_IPSec#Generating_certificates here]. | |||

It would make life significantly easier if there was a graphical utility for generating .csr file. | |||

Use Qt or GTK to build graphical UI and use [https://cryptography.io/ cryptography.io] to interface with the OpenSSL library. | |||

==Pastebin clone [DONE]== | |||

[http://pastebin.com/ Pastebin.com] is a popular website for sharing code snippets via random generated URL-s. Due to security and privacy reasons some teams can not use third party operated websites such as Pastebin.com. It would be nice to have an open-source implementation of Pastebin which could be installed on premises. | |||

* Use [http://falconframework.org/ Falcon] or Flask to implement the API. | |||

* Use plain text files to store the pastes (data/<uuid prefix>/<uuid>/original_filename.ext). | |||

* Use [http://pygments.org/ Pygments] for syntax highlight. | |||

* Add [http://www.captcha.net/ CAPTCHA] for throttling anonymously submitting IP addresses. | |||

* Document how you can run the app under [https://uwsgi-docs.readthedocs.org/en/latest/ uWSGI]. | |||

* optional: Add Kerberos support for authentication with AD domain computers | |||

* Add [https://docs.python.org/2/library/configparser.html configuration file] which could be used to toggle features: anonymous submitting allowed, Kerberos enabled, path to directory of pastes etc | |||

==Chat/video conferencing== | ==Chat/video conferencing== | ||

| Line 247: | Line 1,374: | ||

==Pythonize robots== | ==Pythonize robots [DONE!!!]== | ||

Current football robot software stack is written in C++ using Qt framework. | Current football robot software stack is written in C++ using Qt framework. | ||

| Line 298: | Line 1,425: | ||

software/hardware components and technologies work together. | software/hardware components and technologies work together. | ||

* | * done: Fix nchan support | ||

* easy: Fix Travis CI | * easy: Fix Travis CI | ||

* | * done: Add command-line features | ||

* | * done: Add OpenVPN support, goes hand-in-hand with Windows packaging | ||

* easy: Add Puppet support, goes hand-in-hand with autosign for domain computers below | * easy: Add Puppet support, goes hand-in-hand with autosign for domain computers below | ||

* easy: Add minimal user interface with GTK or Qt bindings | * easy: Add minimal user interface with GTK or Qt bindings | ||

* medium: Certificate signing request retrieval from IMAP mailbox | * medium: Certificate signing request retrieval from IMAP mailbox | ||

* | * done: Certificate issue via SMTP, goes hand-in-hand with previous task | ||

* medium: Certificate renewal | * medium: Certificate renewal | ||

* medium: Add unittests | * medium: Add unittests | ||

* | * done: LDAP querying for admin group membership | ||

* medium: Autosign for domain computers (=Kerberos authentication) | * medium: Autosign for domain computers (=Kerberos authentication) | ||

* | * done: Refactor tagging (?) | ||

* hardcore: Add (service+UI) packaging for Windows as MSI | * hardcore: Add (service+UI) packaging for Windows as MSI | ||

* hardcore: Add [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Simple_Certificate_Enrollment_Protocol SCEP] support | * hardcore: Add [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Simple_Certificate_Enrollment_Protocol SCEP] support | ||

| Line 318: | Line 1,445: | ||

authentication/authorization and firewalls/VPN-s electives next year, | authentication/authorization and firewalls/VPN-s electives next year, | ||

so doing this kind of stuff already now makes it easier to comprehend next year ;) | so doing this kind of stuff already now makes it easier to comprehend next year ;) | ||

==Active Directory web interface== | ==Active Directory web interface== | ||

Latest revision as of 09:54, 10 January 2017

General

The Python Course is 4 ECTS

Lecturer: Lauri Võsandi

E-mail: lauri [donut] vosandi [plus] i703 [ät] gmail [dotchka] com

General

- This is not a course for slacking off

- Deduplicate work - use the same stuff for Research Project I (Projekt I) course or combine it with Web Application Programming (Võrgurakendused I).

- I expect you to understand by now:

- OOP concepts: loops, functions, classes etc

- Networking fundamentals: UDP/TCP ports, logical/hardware address, hostname, domain

- Get along on the command line: cp, mv, mkdir, cd, ssh user@host, scp file user@host:

- (Learn how to) use Google, I am not your tech support

- Of course I am there if you're stuck with some corner case or have issues understanding some concepts :)

- When asking for help please try to form properly phrased questions

- Help each other, socialize, have a beer event and ask me to join as well ;)

- If you're new to programming make sure you first follow the Python track at CodeAcademy, then continue with Learn Python the Hard Way. Videos about Python in general, pygame for game development, PyGTK for creating GUI-s.

- If you need more practicing attend CodeClub at Mektory on Wednesdays 18:00, they usually have different exercise every week for beginners

- If it looks like there is not much Python programming in this course then that sounds like a good conclusion - that's how Python mainly is used in real life, to glue different components together so they would bring additional value. Don't be afraid to learn other technologies ;)

- Learn how to use various string formatting facilities of Python

- Observe Python coding conventions as specified in PEP-8

Grading

As this is elective course there is no grade for this course, it's either pass or fail. There are basically two options for passing the course:

- Pick a project down below or propose your own idea and work on it throughout the semester

- Progress visible in Git at least throughout the second half-semester

- Come for a demo in the labs in May.

- Questions will be asked about the code

- You'll be asked to change the behaviour of your software

- If everything checks out fine you've passed the course

- Take an exam on 26th or 27th of May, the exam consists of:

- Bunch of input files

- Description of expected output

- Snippets how to use suggested Python modules

- Your task is to glue it together and make sure it works

Lectures/workshops

We'll have something for the first half of semester so you would be able to write a Python script that can parse input of different kind, process them and output something with added value (blog, reports, etc):

- Hello world with Python, setting up Git repo

- Working with text files, CSV, messing around with Unicode

- Working with JSON, XML, Markdown files

- Using matplotlib and charting data in general

- Using numpy and scipy

- Interacting with databases

- Building networked applications

- Threads and event loops, running apps under uwsgi, using server-side events

- Regular expressions

- Working with Falcon API framework

- Working with Django web framework, ORM and templating engines

- Network application security

These are the topics to learn if you're afraid to pick anything else below.

Lectures/labs

Lecture/lab #1: file manipulation

In this lecture/lab we are going to see how we can parse Apache web server log files. These log files contain information about each HTTP request that was made against the web server. Get the example input file here and check out how the file format looks like. If you are working remotely on enos.itcollege.ee you can simply refer to /var/log/apache2/access.log

Easily readable version:

fh = open("access.log")

keywords = "Windows", "Linux", "OS X", "Ubuntu", "Googlebot", "bingbot", "Android", "YandexBot", "facebookexternalhit"

d = {} # Curly braces define empty dictionary

total = 0

for line in fh:

total = total + 1

try:

source_timestamp, request, response, referrer, _, agent, _ = line.split("\"")

method, path, protocol = request.split(" ")

for keyword in keywords:

if keyword in agent:

try:

d[keyword] = d[keyword] + 1

except KeyError:

d[keyword] = 1

break # Stop searching for other keywords

except ValueError:

pass # This will do nothing, needed due to syntax

print "Total lines:", total

results = d.items()

results.sort(key = lambda item:item[1], reverse=True)

for keyword, hits in results:

print keyword, "==>", hits, "(", hits * 100 / total, "%)"

Refined version:

fh = open("access.log")

keywords = "Windows", "Linux", "OS X", "Ubuntu", "Googlebot", "bingbot", "Android", "YandexBot", "facebookexternalhit"

d = {}

for line in fh:

try:

source_timestamp, request, response, referrer, _, agent, _ = line.split("\"")

method, path, protocol = request.split(" ")

for keyword in keywords:

if keyword in agent:

d[keyword] = d.get(keyword, 0) + 1

break

except ValueError:

pass

total = sum(d.values())

print "Total lines with requested keywords:", total

for keyword, hits in sorted(d.items(), key = lambda (keyword,hits):-hits):

print "%s => %d (%.02f%%)" % (keyword, hits, hits * 100 / total)

Exercises:

- Try to reduce the amount of lines:

- Improve the log file parsing with CSV reader or regular expressions.

- Improve the counting with Counter object.

- Add extra functionality:

- What were the top 5 requested URL-s?

- Whose URL-s are the most popular? Hint: /~username/ in the beginning of the URL is college user account.

- How much is this user causing traffic? Hint: the response size in bytes is in the variable 'response'.

- Use urllib.unquote to normalize paths.

Lecture/lab #2: directory listing and gzip compression

So far we've dealed with only one file, usually you're digging through many files and you'd like to automate your work as much as possible. At enos.itcollege.ee you can find all the Apache log files under directory /var/log/apache2. Download the files to your local machine:

rsync -av username@enos.itcollege.ee:/var/log/apache2/ ~/logs/

Alternatively you just can invoke the Python on enos:

ssh username@enos.itcollege.ee

python path/to/script.py

Following simply iterates over the files in the directory and skips the unwanted ones:

import os

# Following is the directory with log files,

# On Windows substitute it where you downloaded the files

root = "/var/log/apache2"

for filename in os.listdir(root):

if not filename.startswith("access.log"):

print "Skipping unknown file:", filename

continue

if filename.endswith(".gz"):

print "Skipping compressed file:", filename

continue

print "Going to process:", filename

for line in open(os.path.join(root, filename)):

pass # Insert magic here

You can use the gzip module to read compressed files denoted with .gz extension:

import gzip

# gzip.open will give you a file object which transparently uncompresses the file as it's read

for line in gzip.open("/var/log/apache2/access.log.1.gz"):

print line

Combine what you've learned so far to parse all access.log and access.log.*.gz files under /var/log/apache2.

Set up Git, you'll have to do this on every machine you use:

echo | ssh-keygen -C '' -P ''

git config --global user.name "$(getent passwd $USER | cut -d ":" -f 5)"

git config --global user.email $USER@itcollege.ee

git config --global core.editor "gedit -w -s"

Create a repository at GitHub and in your source code tree:

git init

git remote add origin git@github.com:user-name/log-parser.git

git add *.py

git commit -m "Initial commit"

git push -u origin master

Also create .gitignore file and upload the changes. See example repository here.

Exercises:

- Add extra functionality:

- Create humanize() function which takes number of bytes as input and returns human readable string (eg 8192 bytes becomes 8kB and 5242880 becomes 5MB)

- Use argparse to supply directory path during script invocation and make your program configurable.

Lecture/lab #3: Parsing command-line arguments

Use following to parse the command-line arguments:

import argparse

parser = argparse.ArgumentParser(description='Apache2 log parser.')

parser.add_argument('--path',

help="Path to Apache2 log files", default="/var/log/apache2")

parser.add_argument('--verbose',

help="Increase verbosity", action="store_true")

args = parser.parse_args()

print "Log files are expected to be in", args.path

print "Am I going to be extra chatty?", args.verbose

Now invoke the program with default arguments as following:

python path/to/example.py

Program can be invoked with user supplied parameters as following:

python path/to/example.py --path ~/logs --verbose

Use following to humanize file sizes/transferred bytes, try to make it shorter!

def humanize(bytes):

if bytes < 1024:

return "%d B" % bytes

elif bytes < 1024 ** 2:

return "%.1f kB" % (bytes / 1024.0)

elif bytes < 1024 ** 3:

return "%.1f MB" % (bytes / 1024.0 ** 2)

else:

return "%.1f GB" % (bytes / 1024.0 ** 3)

Use datetime to manipulate date/time information, example here:

import os

from datetime import datetime

files = []

for filename in os.listdir("."):

mode, inode, device, nlink, uid, gid, size, atime, mtime, ctime = os.stat(filename)

files.append((filename, datetime.fromtimestamp(mtime), size)) # Append 3-tuple to list

files.sort(key = lambda(filename, dt, size):dt)

for filename, dt, size in files:

print filename, dt, humanize(size)

print "Newest file is:", files[-1][0]

print "Oldest file is:", files[0][0]

Exercises:

- Add functionality to our log parser:

- What is the timespan (from-to timestamp) for the results? Use datetime.strptime to parse the timestamps from log files.

- Add support for Common Log Format.

- What were the most erroneous URL-s? Hint: Use the HTTP status code to determine if there was an error or not.

- What were the operating systems used to visit the URL-s?

- What were the top 5 Firefox versions used to visit the URL-s?

- What were the top 5 referrers? Their hostnames?

- Advanced:

Lecture/lab #4: GeoIP lookup and SVG images

This time we'll try to make some sense out of IP addresses found in the log file.

In case of a personal Ubuntu machine install additional modules for Python 2.x:

apt-get install python-geoip python-ipaddr python-cssselect

For Python 3.x on Ubuntu:

apt-get install python3-geoip python3-ipaddr

For Mac you can try:

pip install geoip ipaddr lxml cssselect

On Ubuntu you can install GeoIP database as a package, but note that it might be out of date:

sudo apt-get install geoip-database # This places the database under /usr/share/GeoIP/GeoIP.dat

To get up to date database or to download it for Mac:

wget http://geolite.maxmind.com/download/geoip/database/GeoLiteCountry/GeoIP.dat.gz

gunzip GeoIP.dat.gz

Run example:

import GeoIP

gi = GeoIP.open("/usr/share/GeoIP/GeoIP.dat", GeoIP.GEOIP_MEMORY_CACHE)

print "Gotcha:", gi.country_code_by_addr("194.126.115.18").lower()

Download world map in SVG format:

wget https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/03/BlankMap-World6.svg

SVG is essentially a XML-based language for describing vector graphics, hence you can use standard XML parsing tools to modify such file. Use lxml to highlight a country in the map and save modified file:

from lxml import etree

from lxml.cssselect import CSSSelector

document = etree.parse(open('BlankMap-World6.svg'))

sel = CSSSelector("#ee")

for j in sel(document):

j.set("style", "fill:red")

# Remove styling from children

for i in j.iterfind("{http://www.w3.org/2000/svg}path"):

i.attrib.pop("class", "")

with open("highlighted.svg", "w") as fh:

fh.write(etree.tostring(document))

Exercises:

- Add GeoIP lookup to your log parser

- Highlight countries on the world map

- Use HSL color codes to make your life easier

- Commit changes to your Git repository, but do NOT include the GeoIP database in your program source

Lecture/lab #5: Jinja templating engine

In this lab we take a look how we can use Jinja templating engine to output HTML.

In case of a personal Ubuntu machine install additional modules for Python 2.x:

apt-get install python-jinja2

For Python 3.x on Ubuntu:

apt-get install python3-jinja2

For Mac you can try:

pip install jinja2

The template placed in report.html next to main.py:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8"/>

<title>Out awesome report</title>

<link rel="css/style.css" type="text/css"/>

<script type="text/javascript" src="js/main.js"></script>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Top bandwidth hoggers</h1>

<ul>

{% for user, bytes in user_bytes[:5] %}

<li>{{ user }}: {{ humanize(bytes) }}</li>

{% endfor %}

</ul>

<h1>Visits per country</h1>

<img src="highlighted.svg"/>

</body>

</html>

The Python snippet for generating output.html from report.html:

user_bytes = sorted(user_bytes.items(), key = lambda item:item[1], reverse=True)

from jinja2 import Environment, FileSystemLoader # This it the templating engine we will use

env = Environment(

loader=FileSystemLoader(os.path.dirname(__file__)),

trim_blocks=True)

import codecs

with codecs.open("output.html", "w", encoding="utf-8") as fh:

fh.write(env.get_template("report.html").render(locals()))

# locals() is a dict which contains all locally defined variables ;)

os.system("x-www-browser file://" + os.path.realpath("output.html") + " &")

A very lazy way of using single template file with Jinja2:

import codecs

from jinja2 import Template

template = Template(open("path/to/template.html").read())

ctx = {

"filenames": os.listdir("path/to/input/directory")

}

with codecs.open("path/to/index.html", "w", encoding="utf-8") as fh:

fh.write(template.render(ctx))

Exercises:

- Organise your map and HTML template under templates/ directory in the source code tree

- Add command-line argument for specifying the output directory which defaults to build/ in current directory

- Create the output directory if necessary

Lecture/lab #6: Flask web development framework

Following should give a general idea how the Flask works:

# Stuff's missing here of course!

from flask import Flask, request

app = Flask(__name__)

def list_log_files():

"""

This is simply used to filter the files in the logs directory

"""

for filename in os.listdir("/var/log/apache2"):

if filename.startswith("access"):

yield filename

@app.route("/report/")

def report():

# Create LogParser instance for this report

logparser = LogParser(gi, KEYWORDS)

filename = request.args.get("filename")

if "/" in filename: # Prevent directory traversal attacks

return "Go away!"

path = os.path.join("/var/log/apache2", filename)

logparser.parse_file(gzip.open(path) if path.endswith(".gz") else open(path))

return env.get_template("report.html").render({

"map_svg": render_map(open(os.path.join(PROJECT_ROOT, "templates", "map.svg")), logparser.countries),

"humanize": humanize.naturalsize,

"keyword_hits": sorted(logparser.d.items(), key=lambda i:i[1], reverse=True),

"url_hits": sorted(logparser.urls.items(), key=lambda i:i[1], reverse=True),

"user_bytes": sorted(logparser.user_bytes.items(), key = lambda item:item[1], reverse=True)

})

@app.route("/")

def index():

return env.get_template("index.html").render(

log_files=list_log_files())

if __name__ == '__main__':

app.run(debug=True)

Lecture/lab #7: image manipulation and threading

Python imaging library is a module for manipulating bitmap images with Python.

On Ubuntu you can install it with:

sudo apt-get install python-pil

On Mac and Ubuntu:

pip install pillow

Let's say you've travelled abroad and taken a lot of photos with high resolution. It would take ages to upload the images to your favourite website for showing off to your friends. Manually resizing each image is also tedious. You can use Python to write a script for resizing the images automatically. Here is a single-threaded version:

import os

from PIL import Image

d = "/home/lvosandi/images"

output = os.path.join(d, "smaller")

if not os.path.exists(output):

os.makedirs(output)

for filename in os.listdir(d):

if not filename.lower().endswith(".jpg"):

continue

im = Image.open(os.path.join(d, filename))

width, height = im.size

smaller = im.resize((320, height * 320 / width))

smaller.save(os.path.join(output, filename))

Nowadays most processors incorporate many cores onto the same chip, most programming languages however don't support very well taking advantage of such hardware. Threads are one option for making use of multiple cores. We can speed up the resizing by using multiple threads, your milage will vary depending on how many cores your computer has and how fast your permanent storage is. Multi-threaded version of the program above would look something like this:

import os

from threading import Thread

from PIL import Image

d = "/home/lvosandi/images" # This is the input folder

output = os.path.join(d, "smaller") # This is the output folder for small images

filenames = os.listdir(d) # This is the list of files in the input folder

class ImageConverter(Thread): # ImageConverter shall be subclass of Thread

def run(self): # It has run function which is run in a separate thread

while True:

try:

filename = filenames.pop() # Try to get a filename from the list

except IndexError:

break

if not filename.lower().endswith(".jpg"):

continue

print self.getName(), "is processing", filename

im = Image.open(os.path.join(d, filename))

width, height = im.size

smaller = im.resize((800, height * 800 / width))

smaller.save(os.path.join(output, filename))

if not os.path.exists(output):

os.makedirs(output)

threads = []

for i in range(0, 8):

threads.append(ImageConverter())

for thread in threads:

thread.start() # Start up the threads

for thread in threads:

thread.join() # Wait them to finish

On Intel i7-4770R (4 cores/8 threads) you should get something like this with pillow 3.2.0:

We can see that total exection time (real time) drops until we add up to 4 threads without significant increase in CPU time (userspace/kernelspace time). This means the job is distributed along four cores of the machine. Increasing count of threads up to 8 doesn't yeild much improvement in the execution time but CPU time consumption increases most likely because the ALU-s of four cores are shared between eight hardware threads and they have to wait until other thread frees up the ALU. Conclusion: the sweet spot for this kind of workload is 4 threads.

Exercises:

- Add command-line argument parsing with argparse: output directory path and output resolution

- Implement widest edge detection so images can be resized into desired dimensions while preserving aspect ratio

- Implement multithreading for the log parser we've worked on earlier, how much speed up are you gaining?

Lecture/lab #8: subprocess

It seems the audio is missing on the lecture recording so here's a short summary what we did: Mohanad had a demo about the sumorobot v2.0 prototype he had been working on; later I explained more the details of Python multithreading - where it makes sense to use and where not. Due to global interpreter lock only one thread can make use of CPU intensive Python code. Using Python's multithreading makes mainly sense for networking and I/O (eg. urllib) - where the bottleneck is not CPU. You can use subprocess module to push certain tasks to separate processes, thus avoiding the bottlenecks of global interpreter lock.

An example of pushing gzip decompression to separate process with subprocess module looks like this:

proc = subprocess.Popen(["/bin/zcat", "logs/access.log.1.gz"],

stdout=subprocess.PIPE)

fh = proc.stdout

print fh.readline()

for line in fh:

print line

Lecture/lab #9: Regular expressions

Regular expressions are used to match arbitrary strings. For example consider text input field in a HTML5 document:

<input type="text" name="username" pattern="[a-z][a-z0-9]+"/>